Have you ever thought:

- Am I measuring my waist size correctly?

- What does it tell me about my health?

- What is the recommended waist circumference range for optimal health? (prediction and prevention of disease)

Great!

In today's article, you'll learn:

- Why knowing and keeping track of your waist circumference is important if you want to maximize your health and performance.

- about the Body Mass Index (and why it is insufficient).

- The various methods of measuring body composition

- How to measure your waist based on the available scientific guidelines.

Introduction

In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) convened an expert consultation involving prominent scientists and researchers to tackle the escalating issue of obesity and chronic diseases. The consultation also served as a platform to review the progress made in implementing BMI cut-offs specific to the Asian population.

In previous discussions, the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasized the need for additional indicators beyond BMI to assess central adiposity (sometimes also termed as visceral fat, or abdominal obesity in the literature), or in layman's terms, abdominal fat.

This initiative began due to the results of a 12-year-long study of middle-aged men, which showed that waist circumference (measured as waist-to-hip ratio), was associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction (or heart attack), stroke, and premature death. Since then, ethnic-specific criteria for abdominal obesity have been developed by international health organizations such as the Indian Consensus Group, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) of the United Kingdom, and the American Diabetes Association.

Waist Circumference and Health

The relationship between obesity and morbidity risk, especially concerning abdominal obesity, is well-established. Obesity has a profound impact on various aspects of health, including brain function, respiratory health, reproductive function, and significantly increases the risk of debilitating diseases.

It does this through a variety of mechanisms, some as straightforward as having to carry a few extra pounds and some involving complex changes in hormones and metabolism. The condition that is most closely associated with high amounts of abdominal obesity is Type-2 Diabetes, and this has been shown by large-scale epidemiological studies in men and women.

To quote the authors from each study:

"Body mass index was the dominant predictor of risk for diabetes mellitus. Risk increased with greater body mass index, and even women with average weight (body mass index, 24.0 kg/m2) had an elevated risk"

Colditz et al. (1995)

"Weight gain was monotonically related to risk, and for every kilogram of weight gained, the risk increased by 7.3%. A gain in abdominal fat was positively associated with risk, independent of the risk associated with weight change"

Banerjee et al. (2004)

Both of the above collectively mean that a mere 5-kilogram increase in body weight in females, and 7kg in males (or 5.7 inches in waist circumference) is sufficient to significantly increase the risk of diabetes (up to 1.9 and 1.7 times for females and males respectively).

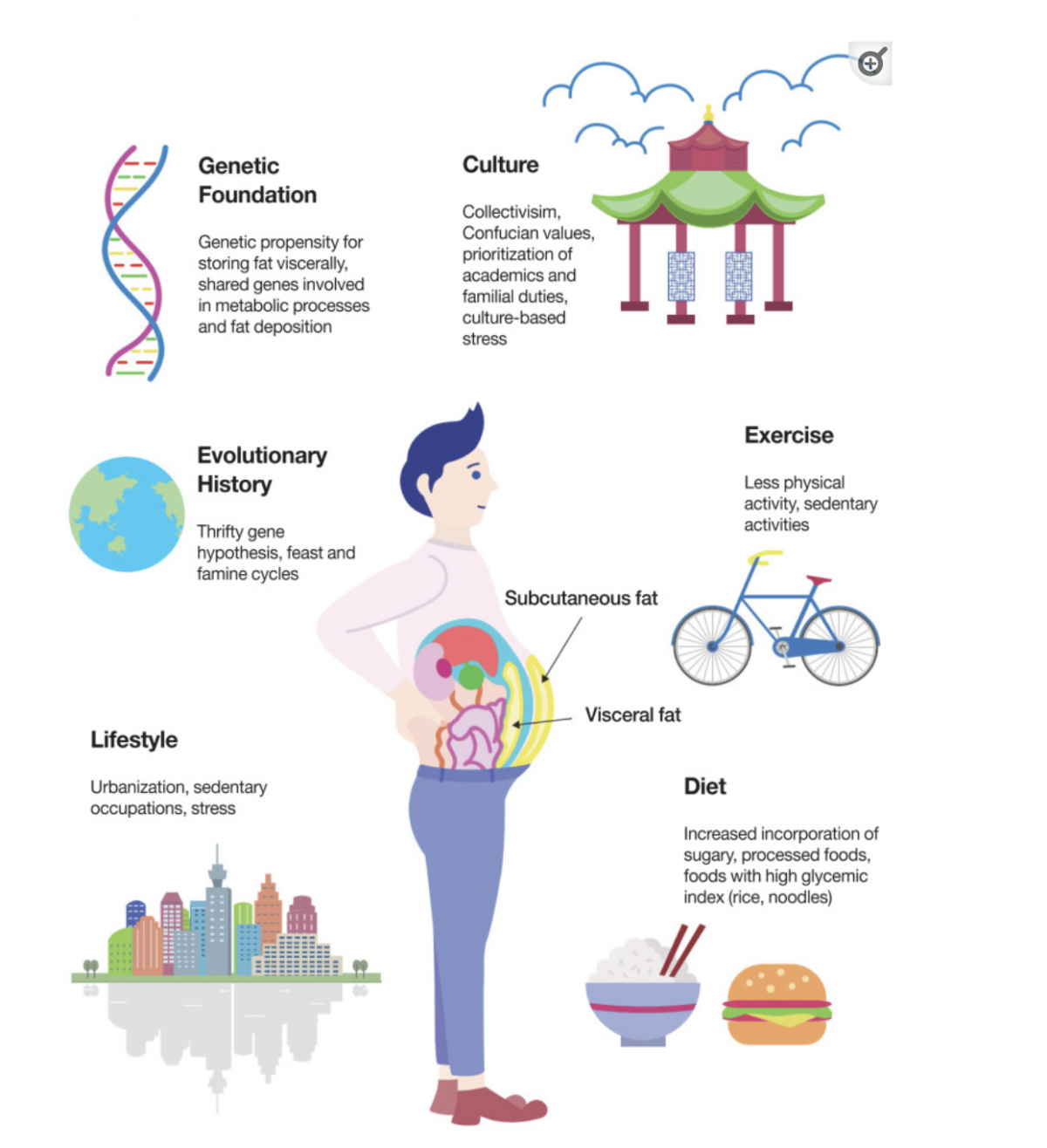

Nevertheless, the risk of Type-2 Diabetes as a result of abdominal obesity can vary across ethnic populations (i.e. Asians vs Caucasians). Strong evidence suggests that Asians tend to have higher abdominal fat mass1 and thus, a higher chance of developing Type-2 diabetes2 at a lower BMI when compared to their Caucasian counterparts.

The reason for this distinction amongst ethnic groups is unclear, with genetic differences cited as one possible explanation (i.e. the thrifty epigenetic hypothesis), while environmental factors have also been shown to be a significant contributor. For instance, a study3 using the data of 7,874 adults born between 1954-1956 showed that experiencing undernutrition in fetal life, such as during the Chinese famine of 1954 to 1964, increases the likelihood of developing diabetes in adulthood, particularly in individuals residing in nutritionally abundant environments later in life.

Together, these two factors create a genetic predisposition for visceral fat accumulation, thereby influencing metabolic processes (how your body converts food, and stores, or uses it for energy).

Now, you must be wondering, what's with abdominal obesity that is so bad? (beyond the superficial part). If you recall, in the introduction, I mentioned that abdominal obesity is linked to the onset of many diseases.

In recent years, the research is unequivocally clear that obesity (mainly visceral obesity) is often accompanied by a cluster of health issues, collectively known as "Metabolic Syndrome" — and studies show as many as 120 million Americans have it.

This condition is diagnosed when 3 of the 5 criteria below are met:

- High blood pressure (>130/85mmHg)

- High Triglycerides (>150mg/dL)

- Low HDL cholesterol (<40mg/dL in men or <50mg/dL in women)100mg/dL or 5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L)xtagstartz/li>

- Waist Circumference* (>40 inches for men, >35 for women)

*Note that this cut-off score is based on studies of the Western population

If you noticed — you don't need to be obese to have metabolic syndrome, as it makes up only 1 out of the 5 criteria above. In fact, some studies have found that 20 to 40 percent of non-obese adults may be metabolically unhealthy, but they are not obese by BMI. This serves as a wake-up call to everyone, it is not only about how much you weigh.

It is worth mentioning that insulin resistance is the hallmark of metabolic syndrome, contributing to its development and progression.

Given that metabolic syndrome is primarily driven by low-grade systemic inflammation, often attributed to the presence of high amounts of visceral fat — it is not surprising that this condition is strongly associated with a range of adverse health consequences affecting various organs such as:

- Cardiovascular/Heart disease (two-fold risk4)

- Cerebrovascular/Brain disease (Alzheimer's/Stroke) (two-fold risk4)

- Certain types of cancers, most notably liver and colorectal cancer in men, endometrial and pancreatic cancer in women5

Is BMI Enough? Other Methods of Measuring Body Composition

Personally, I believe that BMI, in isolation, is insufficient as a marker of obesity and a predictor of cardio-metabolic/morbidity risk. This is especially true in certain individuals with a significant amount of lean tissue (muscle). This is why it is considered a generalized obesity measure by multiple health authorities such as the WHO.

For instance, let's consider a 1.72m, 76kg Asian male with a BMI of 25.6kg/m2. Solely based on this metric and according to the NICE guidelines, which recommend a healthy BMI range of 18.5-23kg/m2 for Asians, this person would be classified as overweight and at an increased risk of diabetes, stroke, and cardiovascular disease.

But what if the person is simply just lean and muscular? (as pictured below). In fact, by this very metric, I would also be classified as overweight — At 1.73m and having a body weight of 71.5kg would put me at a BMI of 23.8kg/m2.

What is Body Composition?

This lack of specificity is why additional tools are needed to determine an individual's body composition — which can be categorized into fat-free mass and fat mass where;

- Fat mass, includes all the fat in your body (i.e. visceral and subcutaneous)

- Fat-free mass, includes bones, organs, water, minerals, etc.

A desirable body composition involves a higher proportion of fat-free mass, particularly muscle mass, and a lower amount of fat mass. On the other hand, an undesirable body composition is characterized by a higher fat mass and a lower fat-free mass, particularly muscle mass.

Assessing body composition is valuable in monitoring weight gain or loss progress as it provides a more comprehensive understanding of overall health and fitness compared to solely relying on body weight.

For instance, let's consider a scenario where you engage in regular exercise and gain two pounds of muscle while simultaneously losing two pounds of fat. In this case, your total weight remains unchanged. If you solely focus on scale weight, you might mistakenly conclude that your diet and exercise routine are ineffective.

Therefore, by paying attention to your body composition, it'll be much easier to recognize the progress you're making.

(Need personalized guidance on setting your lifestyle and training up for success? Apply for coaching here)

Is there a "Best" Way to Measure Body Composition?

Calculating your body composition is relatively simple if you know your body fat percentage, and there are countless calculators online (that use specific formulas) which will help you do that.

However, many of these equations are far more inaccurate than many realize.

Let's take a look at two popular methods of measuring body composition, starting with Bio-Impedance Analysis (see Fig.1 below).

Bioimpedance analysis works by transmitting a weak electrical current through the body and measuring the impedance or resistance. However, extensive research has demonstrated its inaccuracy, which is further influenced by various factors.

Next, we have the Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (DXA), in Fig.2 below, which involves having an X-Ray taken to determine full-body fat and fat-free mass.

Although it is considered the gold standard for assessing body composition. There are a few reasons why I would not suggest the use of DXA, they are:

- Expensive, which may not be feasible to regularly track progress (every 1-2 weeks).

- Prone to individual error, and shown to overestimate decreases in body fat while underestimating increases.

- Produces skewed results if your hydration status changes even so slightly.

These are just two examples among many others, such as the Bod Pod, MRI, and skin-fold calipers.

? Like what you're reading so far and find it insightful?

Stay in the loop and never miss a new post by subscribing to my newsletter here.

Measuring your Waist circumference

While measuring your waist circumference may not specifically target visceral fat, it still serves as a useful indicator of overall abdominal obesity. Besides, it is convenient, reliable, and simple to perform, unlike the previously mentioned options.

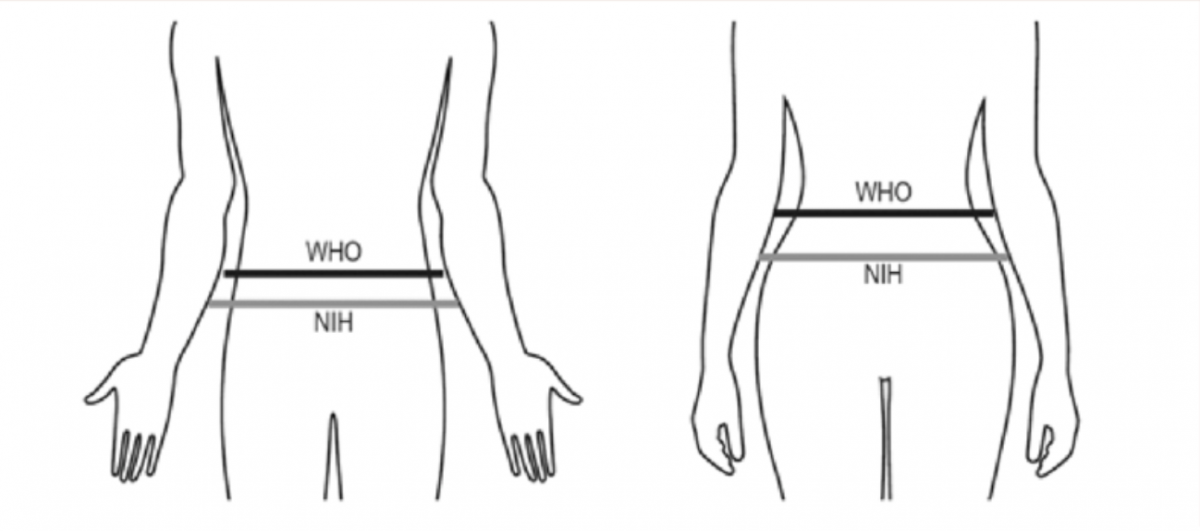

A systematic review of 120 studies in 2008 showed that the waist measurement protocols as per WHO (midpoint between the lower border of the ribcage and your hip bone), and the NIH (at the iliac crest) (see Fig 3) guidelines are feasible and reliable for the general public to take the measurement themselves. Moreover, both showed similar patterns of associations between mortality and morbidity.

Subsequent studies6-9 by other researchers have confirmed that both waist measurement protocols exhibit minimal variations in terms of absolute differences, and are both suitable methods to screen for metabolic syndrome. However, one study conducted by the American Diabetes Association argued that the WHO method provides a better measurement for defining central/abdominal obesity in women.

If I had to choose between the two protocols, I'd recommend using the WHO method of waist circumference measurement — A good approximation for most people is to place your measuring tape just above the belly button and to breathe out naturally before taking the measurement. If you need further guidance, myhealthywaist.org provides step-by-step instructions and is an excellent resource for those who are interested in cardiometabolic diseases.

To begin, scroll down and select the video with the header option 1 "self-measurement", it should look something like the picture shown below.

Measuring Body Composition at home

While waist circumference itself is an excellent measurement to know if you're at risk of certain diseases, I would suggest combining it with the following techniques as they provide a more comprehensive picture of where you're currently at with your training. By considering these numbers collectively, you can then decide to make changes to your workout routine or diet (if any).

- Weekly pictures — sides, back, and front

- Weekly average scale weight — measured first thing in the morning

- Skin-fold caliper testing (refer to Fig. 5)

References

Numbered citations listed above can be accessed here.

Hope you learned something from this piece! You can help me by:

1) Sharing this article with friends and family, if you think it'll help them. Links to share this article on social media channels can be found below

2) If you feel that any of my content is inaccurate, misleading, or out-of-date. Please leave a comment below the article in question.

Marcus Oon

Marcus is a practicing physiotherapist and strength & conditioning specialist located in Singapore. He completed his Undergraduate (Hons) degree at the Singapore Institute Of Technology - Trinity College Dublin, and his Strength & Conditioning certification at the National Strength & Conditioning Association (NSCA). He is also active in the NSCA's Health and Wellness, Powerlifting, and Sports Medicine/Rehabilitation Special Interest Groups.

Found this article informative?